Steamboat Willie Cruises into the Public Domain

By Alison Pringle on April 2, 2024

Leave a comment

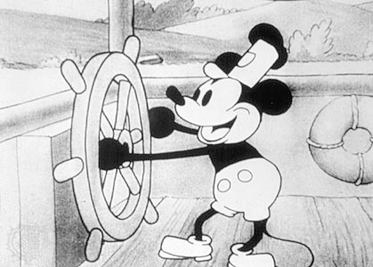

The Copyright Act ensures that its protections extend to creative works even after the death of the author. But no copyright can last forever, and, as of January 1, 2024, an iconic American cartoon has now entered the public domain: “Steamboat Willie.”[i] For those unfamiliar with Disney lore, the cartoon is synonymous with the character we know today as Mickey Mouse. The character was first introduced to audiences (along with girlfriend Minnie) in the 1928 black-and-white animated short film “Steamboat Willie,” directed by Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks.[ii]

Like his fictional comrades Winnie the Pooh, Peter Pan, and Sherlock Holmes, who also recently entered the public domain with much fanfare, Mickey Mouse has gone public. This opens the door to new stories, artwork, cartoons, and more. A horror film featuring Steamboat Willie is already in the works,[iv] and other (hopefully less sinister) adaptations are sure to follow. Of course, any new works using the character would be subject to other intellectual property considerations and a number of caveats.

The character’s entry into the public domain comes 95 years after the release of “Steamboat Willie.” This event is of particular significance because of the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act. Support for the Act from the Walt Disney Company led to the Act being frequently cited as the “Mickey Mouse Protection Act.” Among the Act’s extensions is a provision extending copyright protections to up to 95 years (including renewals) for works created and published before January 1, 1978. Thus, Mickey Mouse served as a quasi-symbol for copyright protection extensions for over two decades. Now, almost a century after his debut, time is up, and the public can use the “Steamboat Willie” version of Mickey.

Members of the public should take care, however, as “Steamboat Willie’s” entry into the public domain would not automatically grant unbridled rights to utilize the Mickey Mouse character. For one, trademark laws would still be in play, preventing the use of a trademark in a manner likely to cause consumer confusion as to source or sponsorship. In short, the question would be whether consumers are confused as to whether unrelated works or products featuring the Mickey Mouse character are affiliated with Disney or made, endorsed, or licensed by Disney. Any potential users would need to tread carefully as Disney still retains a number of trademarks in and related to “Mickey Mouse,” including the name and various logo depictions of the mouse.

As another matter, only the 1928 “Steamboat Willie” versions of Mickey and Minnie have entered the public domain. Copyrighted elements of other works, such as later movies, cartoons, and illustrations featuring Mickey and Minnie, would not have yet entered the public domain. More recent, and, particularly, colorized, versions of Mickey and Minnie would still retain any applicable copyright protections. For instance, Mickey did not obtain his signature white gloves until 1929, and over time his facial features, body parts, shoes, and wardrobe have been changed.[v] The extent to which artists can use Mickey Mouse also presents a new host of legal questions. Copyright law requires a work to possess at least some minimal degree of creativity. Future analysis is sure to focus on the later character elements that are copyrightable (i.e., sufficiently “creative”) and could not be used as compared to pre-existing material from the 1928 versions. The extent that Mickey’s ears, voice, buttoned shorts, or Minnie’s polka dots may be protected under later copyrights, for example, may be parsed out in the years to come as new works are created.

Nonetheless, “Steamboat Willie” is only one of many works that will continue to become available to the public and is certain to pave the way for new creative expression.

*Originally published in the NYSBA Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Journal, Volume 35, Issue 1. Reprinted with permission from the New York State Bar Association © 2024 (www.nysba.org).

About the Author: Alison Pringle is Senior Counsel in the Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani Intellectual Property practice group. Her practice focuses on intellectual property and commercial litigation, with an emphasis on trademark, copyright, contract, technology, and privacy disputes. She also counsels clients on transactional intellectual property issues.

If you have any questions on this recent development or other intellectual property matters, please contact the author or another member of GRSM’s Intellectual Property practice group.

[i] This applies with respect to the United States as copyright laws vary by international jurisdiction.

[ii] Technically, the “Mickey Mouse” and “Minnie” characters first appeared in the animated short film Plane Crazy in 1928, but the film was not widely distributed.

[iii] Walt Disney and Ub Iwerks, “File:Steamboat-willie.jpg,” Wikipedia.org, last modified October 4, 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Steamboat-willie.jpg

[iv] Gene Maddaus, “‘Steamboat Willie’ Horror Film Announced as Mickey Mouse Enters Public Domain,” Variety.com, last modified January 2, 2024, https://variety.com/2024/film/news/steamboat-willie-horror-film-mickey-mouse-public-domain-copyright-1235849861/

[v] Nicole Hellmann, “The Evolution of Mickey Mouse,” The Walt Disney Family Museum Blog, last modified February 3, 2020, https://www.waltdisney.org/blog/evolution-mickey-mouse