Brewery Near Me: Why You Should Name Your Brewery After a Location and Related Trademark Considerations

By Michael Kanach on November 21, 2018

Author: Michael Kanach

Home for the Holidays

Whether you are traveling home for the holidays or visiting an old friend, the holiday season is a time to return to old favorites. For craft beer fans visiting home and looking for a place to gather, they will notice the brewery landscape has changed over the last few years. Whether you are visiting a large city or a small town, the number of new breweries may surprise you. In fact, the number of breweries in the United States has more than tripled recently, increasing from less than 2,000 in 2010 to more than 7,000 in 2018.1 On November 20, 2018, the Brewers Association’s Bart Watson tweeted “Here are the ~1,000 breweries that have opened since last Thanksgiving,”2 with a link to a google map showing new breweries that opened between November 25, 2017, and November 17, 2018.3 In addition, numerous breweries have recently shut down, been acquired, or changed names based on trademark disputes.

Searches for “Brewery Near Me” will be trending on Google and other search engines. For example, when you type “Brewery” into Google.com or Bing.com, both search engines will propose the search “Brewery Near Me.” Alternative results include “Brewery Near My Location,” or nearby city names, such as “Brewery San Francisco” and “Brewery Oakland.” With consumers searching on maps, in search engines, and in beer-focused applications such as Untappd and RateBeer, breweries need to stand out when their name shows up on the list.

From a trademark and branding perspective, you want consumers to recognize your name – and recognize it as a source of great beer. You want your name to communicate the quality of your product and differentiate your brewery from the others in your neighborhood. In other words, you want consumers to know what they can expect when they choose to visit your brewery or drink your beer. Are you known for your rotating selection, your hazy IPAs, your flagship lager, your barrel aged stouts, your sours, or your Belgians? Or maybe you’re known for your food, your staff, or other non-beer-related aspects of running a restaurant or brew pub.

Drink Local = Higher Brand Awareness

When the message is “drink local,” and thousands of smaller breweries are opening up to serve their local communities, it can be beneficial to tell your consumers where you are located. For many breweries, their location is not simply an address in a city or a town. It is also their brand.

In a discussion with Robert Cartwright of DataQuencher, which performs surveys of beer drinkers for breweries, his surveys have shown that location names can help certain breweries increase their brand awareness. The data shows that, for breweries up to about the 20,000 barrels mark, the breweries that have a location in their name have significantly higher brand awareness than other breweries. In other words, microbreweries may benefit from their location-based names, but regional brewers may not see much additional impact.

For example, in Virginia, Blue Mountain Brewery, located in the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains has a higher than anticipated awareness from beer drinkers in the State of Virginia. Given their production numbers (less than 15,000 barrels in 2017) and the size of the Virginia market, it would be normal for Blue Mountain to have a brand awareness in the high 20% to 35% range. Instead, DataQuencher’s recent survey results show that Blue Mountain Brewery has a brand awareness of 49% among VA beer drinkers. This location-based name may also help in each of the states through which the Blue Ridge Mountains extend—namely, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania.

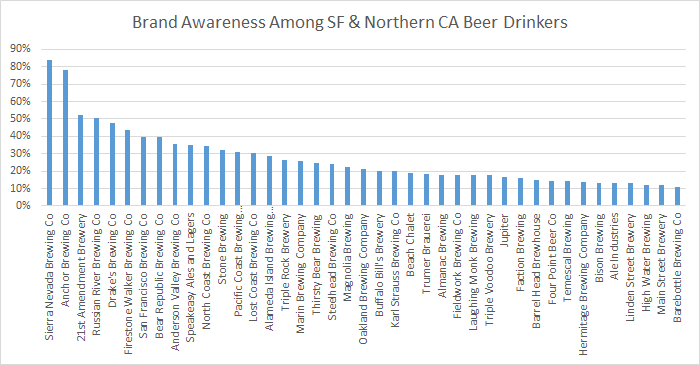

With respect to the San Francisco Bay Area, certain microbreweries rank higher than anticipated in “brand awareness” based on their location-based names, including San Francisco Brewing Co., Alameda Island Brewing Company, Marin Brewing Company, and Oakland Brewing Company. See the recent chart below prepared by DataQuencher. It is not surprising to see some larger breweries with location-based names, such as Sierra Nevada and Russian River, at the top of the list.

Chart reproduced and used with permission.

DataQuencher’s recent survey evidence, which shows higher brand-awareness for breweries with location-based names, is consistent with the breweries who have earned their brand awareness through decades of sales and advertising, as well as distribution through large retail chains and to multiple states. Not surprisingly, many of the largest breweries in the United States have location-based names.4 In fact, about a third (17 of 50) of the Brewers Association’s list of the 50 top selling breweries in the United States in 2017 have location-based names.

The chart below includes a list of those breweries with an explanation of their location-based name for those unfamiliar with the local references. The cites to Wikipedia are because the USPTO will often cite to Wikipedia (or Urban Dictionary!) and other websites as a basis for refusing to register geographically descriptive trademarks.

| Boston (#2) | a city in Massachusetts5 |

| Sierra Nevada (#3) | a mountain range in California and Nevada6 |

| Deschutes (#10) | a river,7 county,8 and National Forest9 in Oregon |

| Brooklyn (#11) | a borough in New York City, New York10 |

| SweetWater (#15) | a creek11 and state park12 outside Atlanta, Georgia (Sweetwater Creek) |

| New Glarus (#16) | a village in Green County, Wisconsin13 |

| Alaskan (#19) | from the state of Alaska14 |

| Great Lakes (#20) | lakes along the border of United States (Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) and Canada (Ontario) |

| Abita (#21) | a town in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, a river (Abita River)15, and nearby springs (Abita Springs)16 |

| Stephens Point (#23) | a city in Wisconsin17 |

| Summit (#25) | a street in Saint Paul, Minnesota (Summit Avenue) |

| Long Trail (#31) | a hiking trail which runs the length of the state of Vermont18 |

| Rogue (#32) | a river19 and a valley20 in Oregon |

| Uinta (#37) | a chain of mountains in northeastern Utah and southern Wyoming (Uinta Mountains),21 a county,22 a reservation,23 and a National Forest24 in Utah |

| Lost Coast (#47) | a coastal region in California25 |

| North Coast (#48) | a region in Northern California that lies on the Pacific coast between San Francisco Bay and the Oregon border26 |

| Wachusett (#49) | a mountain in Massachusetts (Mount Wachusett)27 |

In addition to the chart above, two more breweries in the top 50, DogFish Head (#12) and Allagash (#36), are named after small towns in the State of Maine,28 which – while nowhere close to their brewery locations29 30 – both help tell a story about the brewers’ roots and the breweries’ small beginnings.

How Does a Brewery Obtain a Trademark for its City, Town, Mountains, River, Lake, or Street?

First, a little background about trademarks. Your trademark is your name, logo, or anything else that indicates your brewery is the source of a product or service.

A mark can be:

- a name of a beer or the brewery,

- a drawing (e.g., The Alchemist’s Heady Topper, 21st Amendment’s various can designs),

- a color or color scheme (e.g., Russian River’s Pliny the Elder’s red circle on a forest green label),

- a shape (e.g., Bass’s red triangle, Heineken’s red star),

- a design,

- a slogan, or

- even the unique overall “look and feel” of the brewery, product, or packaging (or other forms of “trade dress”).

You obtain common law trademark rights when you begin to use the mark. If someone else used it first, you are a junior user and they are the senior user. To obtain nationwide rights to your trademark, you can file an application to register your trademark with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”).

One myth is that you don’t want to name your brewery after a location because it’s hard to get a trademark. While it is true that location-based names have inherent hurdles, including from a trademark perspective, there are also potential benefits from a trademark and branding perspective.

Those hurdles include difficulty in proving that your name is an indication that your brewery is the source of the beer. In trademark language, we call that “acquired distinctiveness,” or “secondary meaning.” It may take years for your brewery to build distinctiveness in the eyes of consumers, while a more unique and arbitrary name may obtain a registered trademark much faster.

Because locations are descriptive, the USPTO often refuses to register marks with a location is in the name. On one hand, the USPTO may refuse to register the mark because you are describing where you are located. In that case, the name is “geographically descriptive” and other breweries located there should be able to use that name to describe their brewery. One the other hand, if your name is a location where you are not located, the USPTO may refuse to register your mark on the basis that it is “geographically deceptively misdescriptive.” This means your name makes people believe you are from a location from which your beer does not originate, and that description is misleading and deceptive.

Relatedly, if you advertise your products as coming from a geographic location – but your beer is not from there – those false statements could give rise to a class action lawsuit for false advertising. Numerous lawsuits have been filed over the past several years. For example, class action lawsuits have been filed against Fosters (not imported from Australia),31 Becks (not imported from Germany),32 Kirin (not imported from Japan),33 and Red Stripe (not imported from Jamaica).34 While the breweries named as defendants in those class action lawsuits were some of the largest alcohol producers in the world – Miller Brewing Co. (Fosters), Anheuser-Busch (Becks, Kirin), and Diageo (Red Stripe) – plaintiffs could file similar lawsuits against craft beverage producers as well. So it is wise to clearly label where your brewery (or winery, meadery, or distillery) is located.

To avoid such misrepresentations in labeling and advertising, you will notice the labels for some breweries list more than one location. For example, Lagunitas clearly advertises that it is brewed in Petaluma, California and Chicago, Illinois. Likewise, Sierra Nevada’s labels clearly advertise that it is brewed in Chico, California and Mills River, North Carolina.

While there are many considerations when it comes to branding and trademarks, these are several of the considerations with respect to location-based names. As is the case with all intellectual property, it is prudent to talk to an attorney about your strategy for obtaining and enforcing your trademarks.

For more information about trademarks and intellectual property, you can reach Michael Kanach a partner in the Intellectual Property and Food and Beverage groups at Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani. Mike is also a practice group leader for the Beer, Wine, and Spirits Law group and the Entertainment and Recreation practice group. Mike’s email is mkanach@grsm.com and his phone number is 415-875-3211.

___________________________________________________________________

Purdue licenses its logos and trademarks to Peoples Brewing Company, located in Lafayette, Indiana, for labeling on a beer named “Boiler Gold.” Below left, is an image of the Boiler Gold beer can’s label,16 which contains authorized references to Purdue, a train, and the distinctive letter “P” and the school’s color scheme of “campus gold” and black.17 The infringer’s logo is shown below right, with the University’s name on a black background and underneath a gold and white-colored train.

Purdue licenses its logos and trademarks to Peoples Brewing Company, located in Lafayette, Indiana, for labeling on a beer named “Boiler Gold.” Below left, is an image of the Boiler Gold beer can’s label,16 which contains authorized references to Purdue, a train, and the distinctive letter “P” and the school’s color scheme of “campus gold” and black.17 The infringer’s logo is shown below right, with the University’s name on a black background and underneath a gold and white-colored train. … enjoined to immediately discontinue using or offering or licensing the terms “Purdue”, “Boilermakers”, “Boilermakers Beer” and “Purdue Boilermakers Brewing” or any other marks which feature the words “Boilermakers” and/or “Purdue” for any commercial purpose.

… enjoined to immediately discontinue using or offering or licensing the terms “Purdue”, “Boilermakers”, “Boilermakers Beer” and “Purdue Boilermakers Brewing” or any other marks which feature the words “Boilermakers” and/or “Purdue” for any commercial purpose. In a separate dispute related to the University of Pittsburg (a.k.a. Pitt), a Pennsylvania craft brewery’s use of Pitt’s trademarks is a lesson for brewers to make sure to get written approval from the university before making any substantial investments in labels, bottles, and cans. Voodoo Brewery, located in Meadville, Pennsylvania, began selling a beer under the name “#H2P” with cans designed in Pitts’ colors and script and an image of a cathedral.19 This name “H2P” is short for “Hail to Pitt” and was a trending hashtag for the university during the college football season.20 Pitt owns a registered trademark for “H2P,” which was registered in 2011 and claimed a first use in commerce in 2010. In addition, Pitt owns at least two registered trademarks for “Pitt” with stylized font, and with a distinctive letter “P,” claiming a first use in commerce at least as early as 1990.21 22 Pitt’s colors are royal blue and yellow (or alternatively navy blue and gold).23 The Cathedral is focused throughout the University’s advertising, as shown in the school’s official “Graphic Standards.”24 The letter “P” in the brewery’s “H2P” logo appears to be the same “P” in the University’s registered “Pitt” logo, which has been used for decades.25

In a separate dispute related to the University of Pittsburg (a.k.a. Pitt), a Pennsylvania craft brewery’s use of Pitt’s trademarks is a lesson for brewers to make sure to get written approval from the university before making any substantial investments in labels, bottles, and cans. Voodoo Brewery, located in Meadville, Pennsylvania, began selling a beer under the name “#H2P” with cans designed in Pitts’ colors and script and an image of a cathedral.19 This name “H2P” is short for “Hail to Pitt” and was a trending hashtag for the university during the college football season.20 Pitt owns a registered trademark for “H2P,” which was registered in 2011 and claimed a first use in commerce in 2010. In addition, Pitt owns at least two registered trademarks for “Pitt” with stylized font, and with a distinctive letter “P,” claiming a first use in commerce at least as early as 1990.21 22 Pitt’s colors are royal blue and yellow (or alternatively navy blue and gold).23 The Cathedral is focused throughout the University’s advertising, as shown in the school’s official “Graphic Standards.”24 The letter “P” in the brewery’s “H2P” logo appears to be the same “P” in the University’s registered “Pitt” logo, which has been used for decades.25 According to an October 2017 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Voodoo Brewery’s brewmaster was a former Pitt student and involved in athletics, and the brewery believed it had the University’s approval because the brewery had previously sold these beers on campus.26 However, there was nothing in writing from the University approving the packaging, so the brewery was forced to cease and desist using the schools trademarked hashtag, distinctive name, images, and color scheme.

According to an October 2017 article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Voodoo Brewery’s brewmaster was a former Pitt student and involved in athletics, and the brewery believed it had the University’s approval because the brewery had previously sold these beers on campus.26 However, there was nothing in writing from the University approving the packaging, so the brewery was forced to cease and desist using the schools trademarked hashtag, distinctive name, images, and color scheme.